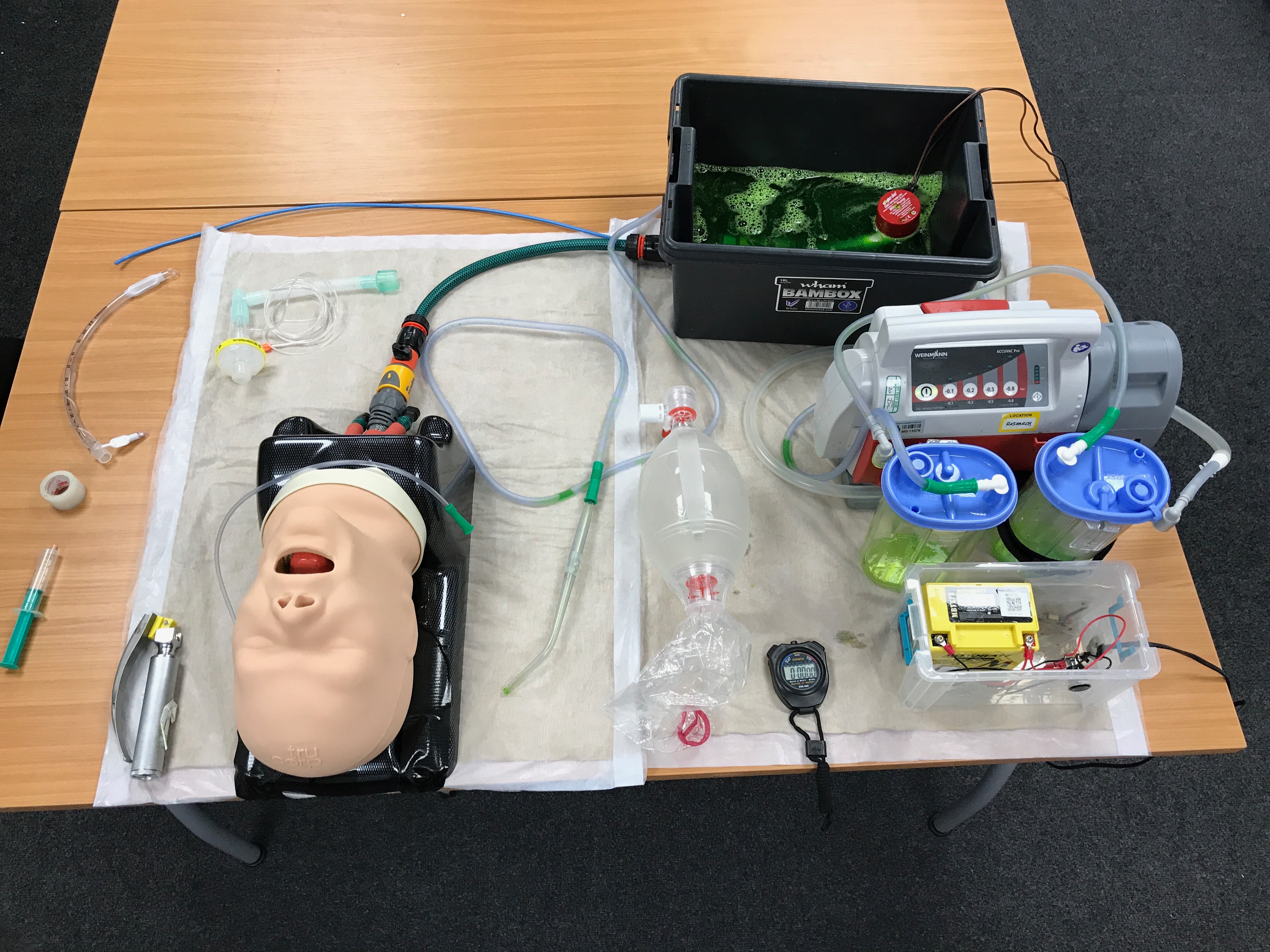

SALAD manikin

A modified TruCorp AirSim Advance airway manikin was used for the study as it has realistic airway anatomy and can be used for tracheal intubation training (Yang et al. 2010). The oesophagus of this manikin was connected, via a hosepipe, to a bilge pump sited within a reservoir of simulated vomit (Figure 3.1). The vomit was water, coloured with food-grade colouring, and thickened with xanthan gum (a food additive). While there are recipes for solid-containing vomit, it was decided that as a first introduction to the technique, thickened opaque vomit would present a sufficient challenge. Once the bilge pump was switched on, a constant flow of vomit was propelled into the oropharynx, obscuring any view of the laryngeal inlet. The flow rate was controlled by a tap, which was calibrated to provide 1 L/min of vomit to the oropharynx of the manikin during intubation attempts. To keep vomit within the oropharynx, the left and right bronchi on the manikin were occluded.

Standard intubation equipment, including personal protective equipment (PPE) and motorised suction routinely used within YAS, was provided for participants, and the study researcher acted as a competent assistant for the intubation attempts.

Procedure

Once informed consent was obtained, paramedics were randomised into either group AAB or ABB. All attempts utilised direct laryngoscopy, which is the standard intubation technique within YAS. Prior to each intubation attempt, the manikin was primed with vomit to ensure the same level of oropharyngeal obstruction. All attempts were video recorded for timing accuracy.

Participants were deemed to have commenced their attempt once the bilge pump was turned on. The attempt was considered to be over when either: the paramedic intubated the manikin and verbally confirmed with the researcher that the attempt had been completed or; 90 seconds had elapsed or; the tracheal tube was placed into the oesophagus and the cuff inflated while the pump was still running.

If the tracheal tube was not in the trachea, with the cuff inflated and connected to a bag-valve device within 90 seconds, the attempt was considered a failure. While it is generally advocated that intubation attempts should take no longer than 30 seconds, this assumes that it is possible to pre-oxygenate patients before an intubation attempt, and re-oxygenate them in the event that intubation is not possible. In patients who have an oropharynx full of vomit, oxygenation is not possible. Therefore a pragmatic and prolonged target of 90 seconds was suggested by Dr. DuCanto (J.DuCanto, personal communication, April 26, 2018).

Participants randomised into the two pre-training attempts group (AAB) made their second intubation attempt immediately following the first, and prior to the group training session. Once all participants completed their pre-training intubation attempt(s), the training session was delivered. The training intervention adopted the Advanced Life Support Group/Resuscitation Council 4-stage approach of skills teaching, comprising (Bullock et al. 2008):

- A real-time demonstration of the SALAD technique by the researcher

- A repeated demonstration with an explanation of the rationale of the steps taken when performing SALAD (not real-time)

- Another demonstration of the SALAD technique conducted by the researcher, but guided by one of the participants

- An attempt by the same participant who guided the researcher in the previous step, followed by a practice attempt by the other participants.

Following the training session, participants made their post-training intubation attempt(s) conducted using the same method as for the pre-training intubation attempt(s). Participants randomised into the two post-training attempts (ABB), made their second attempt immediately following the first post-training attempt.